Why Don’t More Jazz Guitarists Play Nylon Strings Like Charlie Byrd?

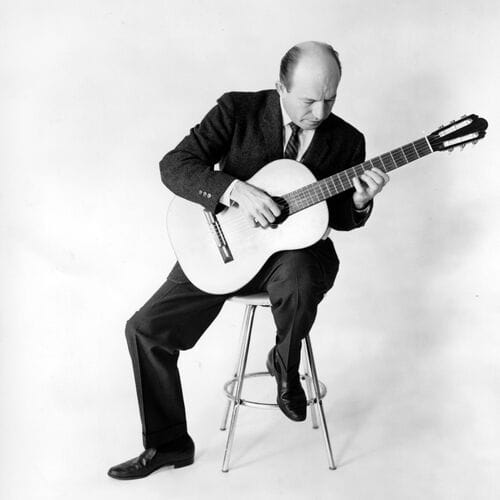

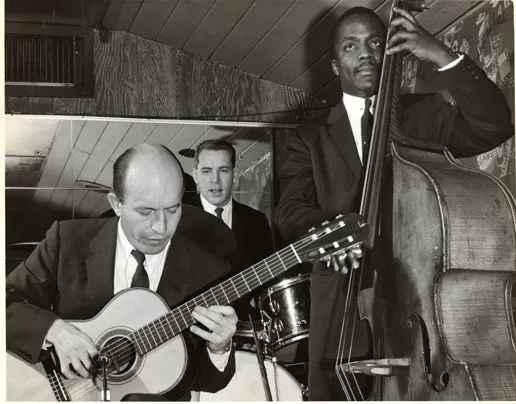

Charlie Byrd holds a unique place in jazz history. He famously played fingerstyle on a nylon-string classical guitar, at a time when most jazz guitarists favored archtop electrics with steel strings. Byrd’s approach was rooted in serious classical study – he trained with Sophocles Papas in Washington, D.C. and even took lessons with the legendary Andrés Segovia in Italy. This classical background gave him a technique and tonal palate unlike his peers. In 1962, Byrd teamed up with Stan Getz to record Jazz Samba, the album that introduced bossa nova to the North American mainstream. Thanks in large part to Byrd, the mellow nylon-string guitar became a voice for Brazilian jazz in the U.S. He “played instrumental roles in helping introduce the nylon-string guitar to jazz and bossa nova to North America”*, carving out a niche for the classical guitar in jazz ensembles.

Byrd’s nylon-string tone stood in stark contrast to other jazz guitar legends of his era. Icons like Wes Montgomery, Joe Pass, and Jim Hall typically played electric guitars with steel strings (often using picks or thumbs) to achieve the warm yet brightly articulated sound jazz audiences were used to.

Byrd, by contrast, drew a pure, gut-string tone from his instrument. The nylon strings produced a rounder, softer attack and a certain classical sweetness. Contemporary guitar experts note that “nylon strings generally have a gentler, warmer, ‘round’ sonic quality”, whereas steel-string guitars sound “bright and vibrant” and can “stand out well in a mix”.

In a small jazz combo setting, Byrd’s guitar offered a lush, intimate sound. His tone could be described as understated – one JazzTimes writer even argued that Byrd’s wide-ranging musical versatility “was never fully appreciated due to the subtle, understated nature of his approach”. Indeed, compared to the punchier, more projecting sound of a typical jazz guitar, Byrd’s nylon-string voice was a different beast altogether.

Nylon vs. Steel: A Tale of Two Tones

The tonal difference between nylon and steel strings is key to understanding why Byrd’s sound was so distinct.

Nylon strings have a smooth, mellow quality with a quick decay; notes don’t sustain or cut through the band as aggressively as steel-string notes do. As one guitar maker puts it, a nylon-string’s sound is percussive but “gentler and less defined than that of a steel-string acoustic”.

Steel strings, especially on an amplified archtop, yield more brilliance and sustain – a singing quality that helps a guitarist be heard alongside drums and horns. Byrd’s contemporaries like Wes Montgomery managed warm tones on steel strings, but still enjoyed the clarity and volume that steel and magnetic pickups provide.

Byrd instead embraced the gut-string voice: a dry, woody tone that may lack bite but offers rich warmth. Listen to Byrd’s recordings (for example, his delicate rendition of “Nuages” or the bossa nova classic “Desafinado”) and you’ll hear that his guitar almost sounds like a classical recital within a jazz context. This was by design – Byrd wasn’t imitating the electric guitar approach at all, but bringing a different tonal concept to jazz. His sound has an intimacy and fingerstyle nuance that sets him apart from the pack of hard-swinging pick-wielders.

Why Don’t More Jazz Players Use Nylon Strings?

If Byrd achieved such a beautiful and singular voice, why did (and do) most jazz guitarists stick to steel strings? Several technical and cultural factors made nylon-string guitars a rarity in jazz:

- Amplification Challenges: For years, amplifying a nylon-string guitar on stage was tricky. Unlike archtop guitars with built-in pickups, classical guitars historically relied on microphones, which can lead to feedback and uneven volume in band settings. As jazz-fusion legend Earl Klugh (one of the few who followed Byrd’s path) recalls of touring in the 1970s: “I had my nylon-string guitar with a very bad pickup – there weren’t any good pickups – and I was dealing with feedback”. Fellow nylon-string jazz guitarist Nate Najar had similar struggles: “I wasn’t happy with any of the ways to amplify the classical. It didn’t sound through an amp the way it sounded… acoustically. I tried a hundred different combinations of pickups, mics, you name it and couldn’t get it where I wanted it”. These technical hurdles made steel-string electrics the practical choice for most gigging players, at least until modern pickup technology improved for nylon guitars.

- Volume and Ensemble Blend: Jazz guitar developed in the big-band era, where the instrument’s role was largely rhythmic comping. Archtop guitars with steel strings (especially when amplified) could cut through a horn section or drum kit with a percussive chunk. Nylon-string guitars, however, tend to be quieter and softer in attack – great for solo or duo work, but easily “drowned out by a full band”. The brighter edge of steel strings helps the guitar stand out in ensemble playing, whereas a nylon-string can disappear in the mix if not carefully miked or amplified. For many jazz bandleaders and guitarists, the path of least resistance was to use the louder instrument that everyone was already accustomed to.

- Technique and Style: Most jazz guitarists are trained to use picks (plectrum) or in some cases thumb-style a la Wes Montgomery. Classic jazz lines – fast bebop runs, bending strings for blues inflection, etc. – are generally easier on steel-string guitars with narrower necks and lower action. A traditional classical guitar has a wide flat fretboard and is meant for fingerstyle playing with no string bending. This makes certain jazz techniques more challenging. As a result, few players in the bebop and post-bop eras attempted to adapt their technique to a nylon-string instrument. Byrd, coming from a classical background, was comfortable playing fingerstyle and didn’t mind the guitar’s wider neck. But a hard-swinging picker like, say, Tal Farlow or Barney Kessel would likely find a classical guitar alien under their fingers. It’s telling that Byrd himself stuck mostly to melodic bossa novas, ballads, and swing tunes that suited his smooth style, rather than rapid-fire bebop ditties.

- Tradition and Cultural Norms: Jazz, like any genre, has its traditions. After Charlie Christian popularized the electric guitar in the late 1930s, the archetype of the “jazz guitar sound” became a warm yet electric tone. Subsequent generations idolized players like Django (who used steel strings), Wes, and others, and they gravitated towards similar gear. The nylon-string guitar, by contrast, was seen as the domain of classical and flamenco music. Culturally, it just wasn’t part of mainstream jazz vocabulary, aside from niche figures like Charlie Byrd or Latin-jazz specialists. Byrd himself enjoyed a successful career, but he was often viewed as a genre-blending outlier rather than the start of a new mainstream trend. As one retrospective put it, he had great popularity and range, but the subtle nature of his nylon-string jazz meant he wasn’t fully emulated by others. The jazz world overall preferred the more direct, punchy sound of steel strings – which perhaps seemed more American jazz and less Euro-classical in character.

Modern Jazz Guitarists on Nylon Strings

While rare, Charlie Byrd did inspire some guitarists to explore nylon strings in jazz. A notable example is Earl Klugh, who emerged in the 1970s blending jazz and pop influences. Klugh was so taken with the classical guitar’s sound that it became his primary instrument. “I always liked the sound of the classical guitar,” he says simply. When Klugh met country-jazz guitar legend Chet Atkins, even Chet was surprised by the choice of instrument: “He was amazed that I was playing a nylon-string guitar exclusively – but he encouraged me in that direction. He said, ‘That’s your instrument.’” With that affirmation, Klugh carried the nylon torch forward, winning Grammy awards and proving that a fingerstyle classical guitar could deliver jazz (albeit in a mellow, smooth-jazz vein).

Another champion of the nylon string in jazz is Gene Bertoncini, often called “The Segovia of Jazz Guitar”. Bertoncini, who came up in the 1960s, is a superb stylist on both nylon-string acoustic and traditional archtop guitar. His ability to swing on a classical guitar in small-group settings (and his gorgeous unaccompanied chord-melody solos) have shown that Byrd wasn’t alone in envisioning the classical guitar as a jazz voice. Bertoncini has noted that today’s pickups and amplification systems (like high-end transducer pickups) have finally made it feasible to amplify nylon-string guitars with a more natural sound, freeing players like him to use the full range of dynamics and tone in larger ensembles.

In the Brazilian jazz realm, nylon-string guitars are actually quite common – after all, bossa nova and samba developed around the nylon-string acoustic. Artists like Laurindo Almeida (who collaborated with American jazzmen in the 1950s), Baden Powell, and today’s Romero Lubambo routinely play jazz and Brazilian standards on nylon-string guitars. Their playing, much like Byrd’s, merges classical technique with jazz harmony. Romero Lubambo, for instance, has recorded extensively with jazz artists, and his nylon-string guitar provides a velvety harmonic cushion in Brazilian-inflected jazz tunes.

Among today’s younger generation, Nate Najar stands out as a direct heir to Charlie Byrd’s legacy. A Florida-based guitarist born in the 1980s, Najar decided to “re-introduce the nylon string to Jazz” and even recorded a tribute album Blues For Night People using Charlie Byrd’s own 1974 Ramirez guitar. Najar approaches the instrument with the same seriousness as a pianist: “I try to treat the guitar like a piano. I don’t think I’ll ever succeed, but my desire is to get a sound like Bill Evans or Vince Guaraldi. I’ve come across plenty of limitations but I assure you they’re with the player and not the instrument!”. This inspiring quote underlines an important point: in the right hands, a nylon-string guitar can swing, sing, and deliver jazz just as effectively as a steel-string. It may require a different touch and mindset, but Najar and others have shown that Byrd’s approach can be modern and relevant.

Other contemporary players have dabbled with nylon strings as well. Jazz fusion icon Al Di Meola has long incorporated acoustic nylon guitars into his music (though often in Latin or world fusion contexts). John Scofield recorded an album (Quiet) using a nylon-string guitar for a more subdued tone color. Even Pat Metheny, primarily a steel-string and electric player, famously played a fretless nylon-string guitar (the Pikasso guitar) on some recordings to achieve unique textures. These examples are exceptions rather than the rule, but they highlight that the nylon sound still holds allure for those seeking its particular expression.

An Overlooked Tone?

Charlie Byrd’s nylon-string jazz guitar remains something of a beautiful anomaly. In an age when most jazz guitarists opt for the bright, readily amplified sound of steel strings, Byrd’s delicate, classical tone can seem almost old-fashioned – or perhaps just underappreciated. We might ask: has Byrd’s tone been unfairly overlooked due to modern jazz’s preference for a punchier guitar sound? His subtle approach did fall out of the spotlight as louder electric guitars came to dominate. Yet Byrd’s recordings reveal a timeless artistry. The nylon-string guitar, in Byrd’s hands, could convey intimacy, swing, and soul in equal measure.

As jazz continues to evolve, there are signs of renewed interest in the sonic possibilities Byrd championed. Younger guitarists like Nate Najar explicitly celebrate Byrd’s legacy, and audiences are rediscovering the warmth and lyricism of the nylon-string jazz guitar. Byrd’s own career was proof that a classical guitar can groove and a quiet approach can still captivate. His legacy invites today’s musicians to rethink the boundaries of jazz guitar tone. Perhaps the rarity of nylon-string jazz guitar is part of its charm – it instantly evokes a different mood and asks the listener to lean in a little more. In any case, Charlie Byrd showed that jazz guitar need not all sound the same, and that beauty of tone can trump sheer volume or bite. His nylon-string explorations opened a door that, while only traversed by a few, remains open for those bold enough to walk through.

In the end, more jazz guitarists haven’t adopted nylon strings because of practical and historical reasons – but those who do carry forward a uniquely inspiring sound. Byrd’s gentle nylon-string voice, once a curious rarity, might yet find its place in future jazz landscapes, ensuring that this elegant tone is never forgotten.